Thin Green Line American Wooden Flag, Military, Rustic ... - us flag green stripe

Participants also completed a few additional questionnaires devised specifically for the present study; the ones we will present are shown in Tables 1 and 2 (Table 2 also indicates which sex-act items were presented to each sex, given their respective genitals). The full questionnaires are available in an appendix to a previous publication (Weinrich et al., 2014, in this issue). Demographic information was also gathered, including age, education, (heterosexual) marital status, employment status, and homosexual relationship status (coupled or uncoupled).

Men’s and women’s attractions to women are remarkably similar. Comparing Figures 2 and 4 chart by chart, the ratings of women’s body parts are very nearly perfect mirror images of each other, as would be expected if this generalization holds. Comparing Figures 6 and 8 chart by chart (where comparable), the ratings of sexual acts with women are often similar—the major exceptions being anal acts, and acts which are qualitatively different for the two sexes (e.g., breast/chest stimulation).

(8) The exhaustive analyses seem to contradict the generalization that among men, nonsexual body parts and non-sexual acts are better correlates of sexual orientation than more explicitly erotic variables are. In the exhaustive analyses, roughly speaking, all these variables differentiate the groups effectively, and sometimes the genital/sexual variables appear to do the best job of this.

With regard to masculine stimuli (men’s bodies and acts with men—bottom half of Figure 10), mean cluster scores of female respondents showed remarkable similarities and differences. Again, anal acts were relatively unpopular, but once again the Bisexual-heterosexual group scored slightly but significantly higher on the anal sex factor than the other groups. The erotic acts factor showed a pattern which was nearly a perfect mirror image of that ascertained for the sexual acts factor for sexual contact with women: the three non-lesbian groups being about equally excited by erotic acts with men, and the Lesbian cluster obtaining a much lower average score (albeit one with a high standard error). Interestingly, the non-erotic but affectionate acts factor did not vary by sexual orientation cluster! When it came to the factors describing men’s body parts, only the genitalia were of significantly different excitement value across sexual orientation clusters; men’s nonsexual body parts, their hirsutism, and their torso muscularity were not differentially exciting across sexual orientation clusters.

Finally, we assessed the significance of group differences using ANOVAs and nonparametric statistics (where appropriate).

This pattern suggests that men and women differ significantly about what it is about men’s bodies that is attractive to them. The contrast with finding (1) is quite clear. Even the non-exclusively heterosexual men differ quite a bit in their ratings of masculine stimuli (androphilic versus genital/ephebephilic traits, for example).

A participant’s KSOG Present Self-Identification as heterosexual, bisexual, or homosexual on a scale ranging from 1 to 7 is shifted just one point away from what most studies measure when they ask participants to identify their sexual orientation on a Kinsey-like scale (0 to 6). By this criterion, we succeeded in attracting a sample that is only moderately biased toward heterosexual participants (Table 3). Just over 40% of the sample is completely or nearly completely heterosexual, the others being distributed across the rest of the sexual orientation spectrum. The women are twice as likely as the men to report that they are equally homosexual and heterosexual (i.e., bisexual); the men are over 4 times as likely to report that they are entirely homosexual. This finding is consistent with other studies (for a review see Weinrich, 1987/2013, pp. 41–42).

Men’s and women’s attractions to men are very different, especially men’s body parts. Comparing Figures 3 and 5 (male body parts) chart by chart shows that corresponding charts are rarely mirror images of each other. Comparing Figures 7 and 9 (sex acts with men) one again sees only occasional similarity in the (mirror images) of corresponding charts.

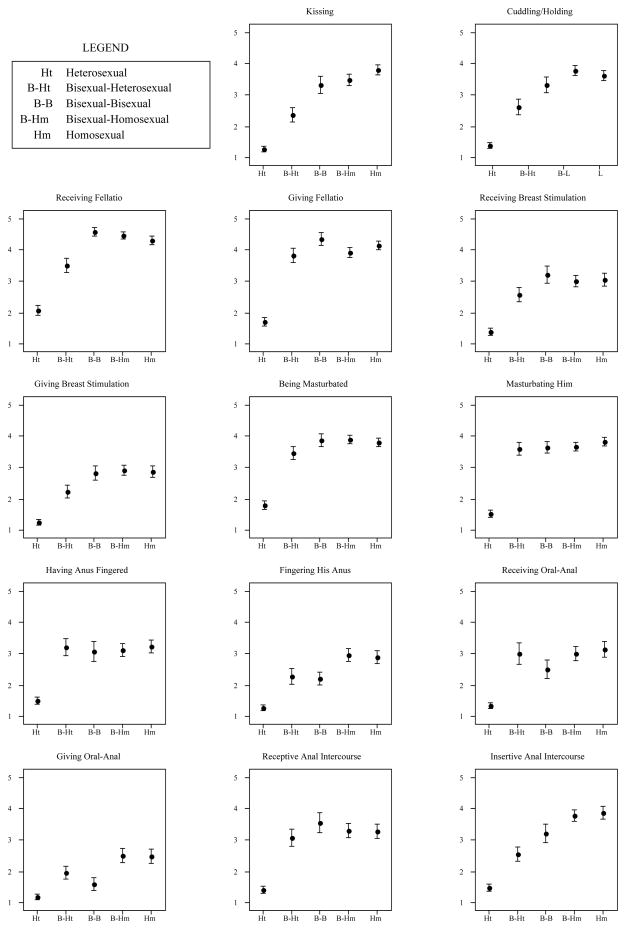

For each of the 12 parts of the body, there is almost never any significant difference between the Bisexual-lesbian group and the Lesbian group, and rarely any difference between the Heterosexual and Bisexual-heterosexual groups. There is far more variation between groups in ratings of the genitalia (penis and testicles/scrotum) than there is for the other body parts. There is somewhat more variation for androphilic traits (muscular torso, small buttocks) than for other body traits such as face and legs. In nearly every instance, the standard error for the Lesbian group is substantially higher than it is for any of the other 3 clusters.

Both sexes run counter to stereotypes in the generalizations above. This suggests the following hypothesis that may restore some truth to those stereotypes. Note that these analyses were conducted within gender, for both men and women. It may still be true that most men attribute higher salience to genital than to affectionate acts (or body parts), but our comparisons were only among men. Thus there may perhaps be little difference by sexual orientation cluster in the importance men attach to genital acts (or the genitalia), and what distinguishes men from each other is affectionate acts (and the less specifically genital parts of the body). Likewise, it may still be true that most women attribute higher salience to affectionate acts (or non-sexual body parts) than to genital acts (or the genitals), but the items distinguishing women from each other are those more specifically genital and erotic acts and parts. Nevertheless, we find these patterns striking.

Papers in this series should be regarded as resulting equally from the intellectual contributions of the two authors, who agreed to exchange first and second authorship with each successive publication.

The ratings of men’s body parts by men revealed a quite different factor structure. The Nonsexual factor came first (i.e., explained the largest proportion of the variance), followed by a combination of two Androphilic variables—large buttocks and much body hair. The third factor, Genital/Ephebephilic, comprised the genitalia, small buttocks, little body hair, and a non-muscular torso—all characteristics of male youths (in Greek, ephebes, hence the name). Note that although the loadings for “Penis” and “Testicles/scrotum” loaded onto the “Ephebephilic” factor, their loadings on the “Genital/Androphilic” factor were not small. Likewise, “Body hair: little or none” loaded most strongly on “Ephebephilic”, but also loaded strongly on “Nonsexual”.

It would thus seem that even though high ratings of feminine stimuli are a majority preference for men and a minority preference for women, the men and women who find women sexually exciting agree about what it is that is exciting about those feminine stimuli. Men and women who are excited by feminine stimuli tend to be excited by specifically sexual body parts, by nonsexual body parts, or both (hence, the statistical independence of those two factors). In sex acts, they may be stimulated by sexual/affectionate acts, anal acts, or both—but they seem to make little distinction between sexual and affectionate acts in reporting what they find stimulating.

New, Old Stock LOS ANGELES CITY FLAG (California) 5 ft x 8ft Nylon Fabric. Screen Printed Seal, Applique Stitched into flag. Pole Sleeve heading. Only one flag ...

This could be due to any of a number of factors. In our culture, as a general rule, women are permitted more freedom to stray from the socially prescribed heterosexual path than men are. Accordingly, there may be more women with some heterosexual arousability diluting, in some sense, the otherwise purely lesbian cluster.

... Bahamas through The Bahamas National Trust, a statutory body set ... The Flag of The Bahamas The symbolism of the flag is as follows: Black, a strong colour ...

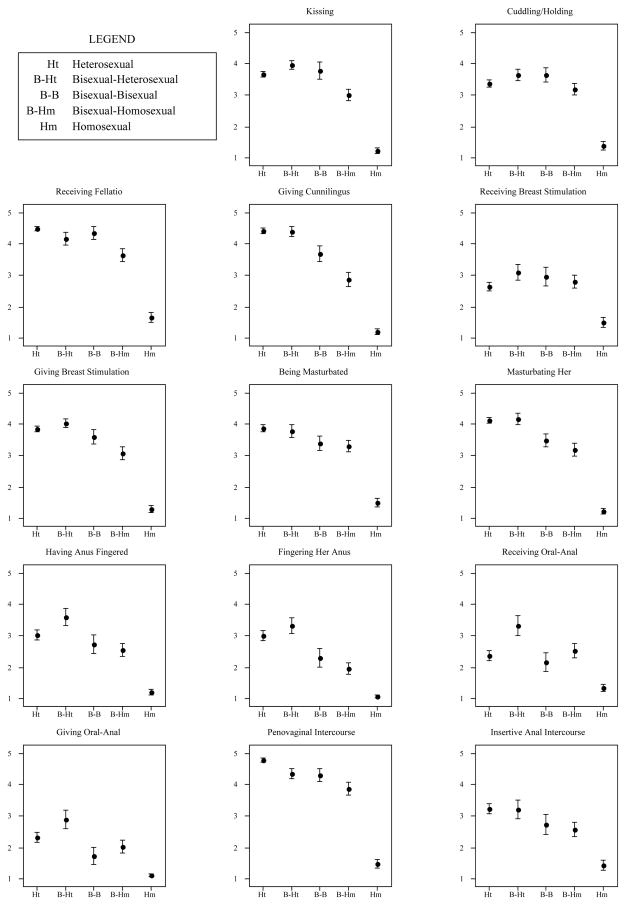

With regard to masculine stimuli (men’s bodies and acts with men—bottom half of Figure 11), the patterns were remarkably similar for the nonsexual parts of the body and the affectionate acts with men: heterosexual group members (of course) rated these factors the lowest, Bi-heterosexual group members rated them a bit higher, and the remaining bisexual and homosexual groups rated them the highest (and not significantly different from each other). The ratings of anal sex with men were, again, a bit high for the bisexual-heterosexual group, by comparison with ratings from the other four groups (which fell into place nearly in a straight line as one might expect). The erotic acts with men showed a familiar pattern, with the four non-heterosexual groups rating this factor about equally high, and the heterosexual group much less.

With very low standard errors, the Heterosexual cluster, not surprisingly, averaged significantly lower scores than any of the other clusters on all 14 of the male-male acts mentioned on the questionnaires. The Bisexual-homosexual group’s averages never were significantly different from the Homosexual group’s averages. The Bisexual-heterosexual and Bisexual-bisexual groups rarely differed from each other, and were either intermediate in value or closer to averages for the more homosexual groups. Contrary to patterns mentioned above, acts involving the anus showed no anomalies by cluster membership.

Below, we describe the sampling and cluster analyses only briefly, because they have been previously detailed (Weinrich & Klein, 1997). We then report mean scores and standard deviations for each of the clusters on a series of questions concerning the erotic valence of various sexual acts and parts of the body. Finally, we discuss the meaning of these results and draw conclusions about the nature of sexual orientation variability in our samples.

As mentioned in the Results section, on the male side it is also important to note how separate factors emerged for androphilic and ephebephilic traits (i.e., a distinction between fully masculinized adult men and masculinizing youths). It is a stereotype held by many people that youthfulness is especially emphasized and prized in gay male culture. But this stereotype overlooks much variability. There is no doubt that the boyish youth is one popular archetype; the fact that the ephebephilic traits on our questionnaire (slim body, absence of body hair) load on the same factor as the male genital traits (penis, testicles) suggests that this archetype is widely desired. But the emergence of a separate androphilic factor (body hair, torso muscularity) warns us against oversimplification.

For the present paper, we conducted two sets of analyses: an exhaustive set and a data-reduced set. Because the exhaustive set consisted of a large number of analyses, we ran the risk that we might lose statistical power by virtue of conducting too many statistical tests. We consider these results to be suggestive, and thus do not present values for statistical significance in them (although readers are invited to pay attention to the standard-error bars shown in the charts to help discern which differences are likely to be statistically significant). The data-reduced set is the one upon which we conducted formal statistical tests; we believe that trends deduced from these data are likely to be stronger. The organization of the analyses was as follows:

For the men’s body parts (Table 5), 4 factors emerged for female respondents and 3 for the males. For females’ ratings of men’s body parts, we termed the factors Genital (consisting of the penis, testicles, and large buttocks); Non-sexual parts such as face, hair, legs, and small buttocks; Hirsutism of the chest (with “little or none” and “a great deal” entering as a contrast factor with opposite signs); and Torso Muscularity (again, a contrast factor, with the two variables entering with opposite signs).

With regard to feminine stimuli (women’s bodies and acts with women—top half of Figure 11), mean cluster scores of male respondents revealed intriguing contrasts and similarities. The Affectionate/Sexual acts with women were equally (or nearly equally) exciting to the heterosexual and bisexual male respondents, and of course far less exciting to the homosexual participants. A similar (albeit weaker) pattern was revealed in the ratings of the nonsexual parts of women’s bodies, whereas a straight-line relationship was revealed in ratings of the erotic (gynephilic) body parts. Anal sex with women was most highly rated by the Bi-heterosexual men, and least highly rated by the homosexual men, with heterosexual and the other bisexual groups in between—highlighting and validating a generalization discernible in the exhaustive analyses.

20171130 — The UNT Battle Flag was created by Jim Hobdy ('69) while he was an employee of the UNT athletics department in 1986. As director of marketing, ...

James D. Weinrich, PhD, is currently the editor of the Journal of Bisexuality. He collaborated with Fritz Klein on some innovative studies of bisexuality in the early years of the Journal.

For each of the 10 parts of the body, there is often no significant difference between the Bisexual-heterosexual group and the Heterosexual group, and often no difference between the Bisexual-heterosexual group and the Bisexual-bisexuals. The exclusively Homosexual group, as might be expected, always averages significantly lower ratings than all 4 of the other groups on these heterosexual stimuli, especially concerning the genitalia (clitoris, labia, and vagina). The Bisexual-homosexual group is always intermediate between the more heterosexual and homosexual groups.

(9) Among female respondents, the biggest differences in attractions to men by sexual orientation pertain to specifically erotic differences—penovaginal sex, being masturbated by a man, and men’s genitalia—not merely affectionate acts or the less overtly sexual parts of the body (with the possible exception of small buttocks). This is particularly evident when one observes (9a) that the female sexual orientation groups differ quite a bit in their ratings of female body parts, but much less in their ratings of male body parts (compare Figures 2 and 3).

For the sex acts with women (Table 6), 2 factors emerged (again, in both male and female subsamples)—which we termed Affectionate/Sexual acts and Anal acts. Nearly identical factor loading patterns emerged for male and female respondents in both cases (taking account of the details of each possible combination of genitalia), with very similar eigenvalues and variances.

For the body parts of women, only 2 factors emerged—and these two were nearly identical for both female and male respondents (see Table 4). They were Gynephilic/Sexual traits (consisting of the genitalia, large breasts, and large buttocks) and Non-sexual parts (such as the face, hair, and legs, and the less definitively feminine choices of “Breasts: small” and “Buttocks: small”). Even the eigenvalues and variance proportions were remarkably similar in female and male subsamples. The only interesting difference, perhaps, is the fairly high loading of 0.528 in the male sample for the “Breasts: small” item in the Gynephilic/Sexual factor (it loads with an even higher value of 0.670 on the Non-sexual factor, which is why we assigned it to that latter factor). This suggests that for men, although large breasts are perceived as a feminine erotic feature, small breasts have enough enthusiasts to cause the “Breasts: small” item to load heavily on both factors.

Gynosexualflag

Lesbian group variability is usually much higher than in any of the other groups. This high variability is especially obvious when contrasted with the low variability seen among the homosexual men, and cannot be accounted for simply by sample size. We remarked above that in more than one way, women are more likely to be bisexual than men (a conclusion which is admittedly subject to a variety of definitions of the word bisexual, as previously cited; see Weinrich 1987/2013, pp. 41–42). It is worth pointing out that even though a cluster analysis would have permitted such a “purely” lesbian cluster to emerge, it did not emerge in our sample. The Lesbian cluster in our sample must have contained some women who had some substantial interest in the body parts of men, and in sexual relationships with them.

(5) Bisexual individuals are neither consistently intermediate between homosexual and heterosexual individuals nor consistently similar to homosexual individuals and heterosexual individuals.

For the data-reduced analyses, we replaced the 50 dependent variables with scores created from factor analysis. We conducted factor analyses (separately by each combination of sex of target and sex of respondent) of the 28 items pertaining to sexual activities (14 for each sex), and then the 22 items pertaining to the erotic value of different parts of the body (12 for men and 10 for women). The factor procedure was principal component analysis using varimax transformation.

Which parts of the body? Which sexual acts? We address this question empirically through a factor analysis of people’s ratings of the attractiveness of women’s and men’s body parts, and of particular sex acts with men and women. Participants of a wide variety of sexual orientations (including a rich sample of bisexuals) rated body parts (by sex) and sex acts (by sex) on 1-to-5 scales. We factor-analyzed answers to these 50 questions to reveal the factor structure of people’s attractions as a function of their sexual orientation (itself derived from a previously reported cluster analysis of the Klein Sexual Orientation Grid), then calculated average responses of the male and female clusters on the factors that had emerged. The data showed: (1) The factor structure of men’s and women’s attractions to women were remarkably similar. (2) The factor structure of men’s and women’s attractions to men’s bodies were remarkably different, identifying an attraction to adult masculinity that differed from attraction to adult boyishness. (3) Lesbian group variability was usually much higher than in any of the other groups. (4) Even though our sample was intentionally diverse, many of our participants only reported attractions to members of one sex. (5) Bisexuals were neither consistently intermediate between homosexuals and heterosexuals nor consistently similar to homosexuals and heterosexuals. (6) Bi-heterosexuals (one of 3 bisexual subgroups) seemed to be more sexually adventurous than might be expected from their position in the progression from pure heterosexual to pure homosexual, especially with regard to anal sex (albeit moderately so). (7) Homosexual men were not intrinsically attracted to anal sex per se. (8) Among men, nonsexual body parts and non-sexual acts were picked out in factor analyses and explained somewhat more variance between men of different sexual orientations than explicitly erotic variables do. (9) Among female respondents, the biggest differences in attractions to men by sexual orientation pertained to specifically erotic differences, not affectionate or bodily stimuli. (10) Although oral-anal contacts generally received low ratings by all the groups of women, ratings of oral-anal contacts were particularly low among lesbians.

There were 14 male-female sexual interactions for which we gathered data. The five acts involving anal contact or manipulation were rated as less exciting than most of the other eight acts. However for 4 of those 5 members of the Bisexual-heterosexual group reported that they were on average significantly more excited by such acts than any of the other four clusters were! Anal acts aside, the Heterosexual group averages did not ever differ from the Bisexual-heterosexual averages except (barely) for penovaginal intercourse. The Homosexual group always scored significantly lower (sometimes a great deal lower) than the other clusters did on all of these male-female acts—and always with very low standard errors (unlike the case with male-female acts and the Lesbian cluster). The Bisexual-bisexual and Bisexual-homosexual clusters sometimes scored in the intermediate range, but usually closer to the averages of the Heterosexuals.

There was an extremely interesting pattern in the ratings of the “androphilic” body parts (hairy body, muscular torso) and the “ephebephilic” body parts (unhairy body, boyish torso). Of course, the Heterosexual group members tended to have low scores on both scales, and the Homosexual (and Bi-homosexual) group members had high scores. But for the androphilic factor, the Bi-heterosexual and Bi-bisexual groups averaged scores just as low as the Heterosexual group did; on the ephebephilic factor, they scored as high as the Homosexual group did. This suggests that a distinction between males seeking masculine partners and those seeking boyish partners may be an important one in the male gay/bisexual community. It is tempting to speculate that the ephebic body type is somewhat more attractive to bisexual men because in certain respects it resembles the body type of women.

It was Dr. Klein’s idea to investigate whether various parts of the body were equally attractive to people of various sexual orientations. It was my idea to extend this to sex acts and relationship types (insofar as the various body-part combinations would allow), and to use cluster analysis and factor analysis to reduce the data to statistically manageable proportions. Once the data were gathered and analyzed, the four above-mentioned papers were written.

Another intriguing finding is that the Bi-heterosexual group (among both men and women) seems on average to be somewhat (albeit not extremely) more sexually adventurous than would have been predicted by most theories, especially when it comes to acts involving anal contact.

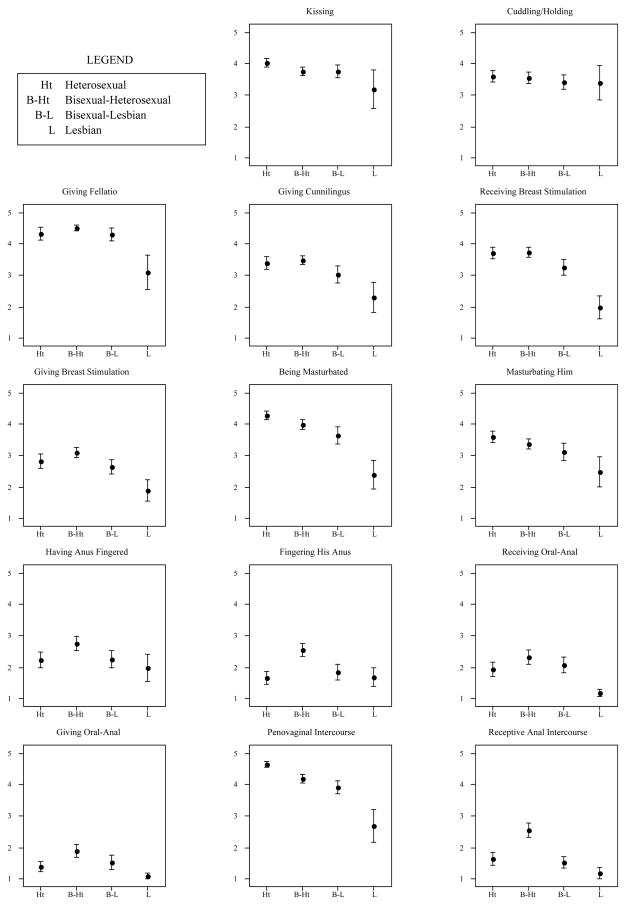

Perusing the charts in the Exhaustive Analyses for the female participants, we see confirmation of many findings from the Data Reduced Analyses. In particular, the following conclusions from the Data Reduced Analyses are directly confirmed. (For the convenience of readers who have devoured everything so far, we highlight findings in italics below if they have not been mentioned previously.)

It stands to reason that men’s attractions on the basis of the specifically sexual and the not-so-sexual acts and parts of the body are correlated in the raw data. Once one of these two aspects is identified in the factor analysis as the most important, much of the variance associated with it is statistically removed from the dataset. In two different factor analyses, two rival factors may thus emerge, each emerging first in one of the two analyses, and each relegating the other to an eigenvalue of much lesser value in the corresponding analysis—even if the two samples are only a bit different from each other.

Among female respondents, the biggest differences in attractions to men by sexual orientation pertain to specifically erotic differences, not affectionate or bodily stimuli. In Figure 10, the only really large differences by sexual orientation are those pertaining to specifically erotic sex acts, with the lesbian women being (as expected) far less interested in such acts with men than the other three sexual orientation groups are. More surprisingly, there are no significant differences by group in women’s ratings of affectionate acts with men! If the Bi-heterosexual group of women had not given significantly (albeit modestly) higher ratings to anal sex with men there would be no differences among the anal acts, either.

Of course, generalizations (1) and (2) cannot be directly addressed by the exhaustive analyses, because they pertain to the factor analyses. Nevertheless:

Among men, nonsexual body parts and non-sexual acts are highly salient correlates of sexual orientation—perhaps even more salient than more explicitly erotic variables are. The first factor (highest eigenvalue) emerging for male body parts (as rated by men) was the non-sexual parts factor. The first factor emerging for acts was affectionate acts like hugging and kissing. This pattern suggests that an interest in having sex with a man, or having an interest in his genitalia, are less important in “determining” sexual orientation than receiving love or affection from a man.

So was Woody Allen right? Does being bisexual double your chances for a date on Saturday night? For some types of bisexual people, the answer is apparently yes—especially the Bi-heterosexual group members. For other bisexuals, the answer may also be yes, but the outlook is much less clear. The next paper in this series will examine this sample’s ratings of different sexual relationships (pairings, “three-ways,” etc.) and yield further insights into this type of question.

For each of the 12 parts of the body, there is never a significant difference between the Bisexual-homosexual group and the Homosexual group. The Heterosexual group always averages significantly lower than the others do concerning these male stimuli. The Bisexual-heterosexual and Bisexual-bisexual groups’ averages are either not much different from the Homosexual group’s averages or are intermediate between those of the Homosexual group and the Heterosexual group.

In this paper, we have presented a great deal of data—so much that it may seem futile to try to condense it and reach succinct conclusions. But this is specifically why we conducted the Data Reduced analyses. Accordingly, we will summarize and make suggestions first using our Data Reduced analyses and the factor analyses upon which they were based. Then we will move on to discuss further insights from the Exhaustive analyses.

Arguably the most intriguing finding is that men’s and women’s ratings of excitement from feminine stimuli (sex acts with women and women’s body parts) show very similar underlying structure, whereas their ratings of masculine stimuli show very different structure. This is presumably related to our finding that women’s ratings of the non-genital parts of men’s bodies didn’t differ much by sexual orientation, but that men’s ratings of most parts of men’s bodies differed quite a bit by sexual orientation.

We are not all bisexual. One common slogan, or intellectual notion, is that “we are all born bisexual” and that homosexuality and heterosexuality result when people are forced to choose one gender over the other. We cannot address this notion of forced choice directly and there may be some truth in it, but our data do suggest that if we are indeed all “born bisexual,” then we do not remain that way. Even though we biased our recruitment efforts towards individuals who would show a fair amount of responses to stimuli of both men and women, there were many participants who did not report any attraction to members of their non-preferred sex. Of course, the extent to which this is true depends on the precise definition of bisexuality that is used.

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

2024929 — The large yellow star represents the Communist Party, and the four smaller stars represent the social classes within the country.

USAFWC & NELLIS AFB PHOTOS · History behind Air Force guidon · Quick Links · Careers · Connect. Get Social with Us.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

In these analyses, we discuss factor scores (not individual questionnaire items, which were discussed above) as a function of cluster membership for each gender separately.

2019829 — I observed on one of the drums belonging to the marines now raising, there was painted a Rattle-Snake, with this modest motto under it, 'Don't ...

Participants completed the Klein Sexual Orientation Grid (or KSOG), an instrument first described scientifically in this Journal (Klein, Sepekoff, & Wolf, 1985). As shown in Figure 1, this questionnaire consists of 21 items grouped into 7 variables; for each variable, participants rate themselves 3 times (for Past, Present, and Ideal) on a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 indicates the most other-sex or heterosexual response and 7 represents the most same-sex or homosexual response.

The number of factors was chosen to match the number of eigenvalues greater than 1.0 (which varied, of course, from analysis to analysis). Eigenvalues and proportion of variance accounted for by each factor are listed at the bottom of the corresponding column of loading values.

For both male and female respondents, ratings of female body parts loaded onto a nonerotic factor and a gynephilic/erotic one. Once again, that was all—no finer distinctions. Factor loadings and variances accounted for were remarkably similar across gender of respondent.

With such a wealth of detail, seeking patterns might seem a futile exercise. Yet there are many interesting generalizations that emerge from this dataset.

Let us briefly describe factor analysis for readers who may be unfamiliar with this insightful exploratory statistics technique. How do psychologists know, for example, that there are two types of anxiety: state-based anxiety and trait-based anxiety? Are those two types merely an idea for two categories that sprang from the fertile mind of the experts, an idea then embedded in a questionnaire whose concepts were generated, so to speak, from the “top down”? Or do they emerge from the data, naturally, objectively, from the “bottom up”, based on the data themselves and not on a human being’s presumption of knowing about the nature of anxiety?

20211011 — The colours of the central motif are blue for peace, and yellow for equality, justice and hope. The Pan-African flag. In 1920, Marcus Garvey, ...

It may be that individual bisexuals are truly more complex than typical monosexually-oriented people are (monosexuals are by definition excited by a single gender: i.e., homosexuals and heterosexuals). Thus it may simply be more difficult to define types of bisexuals, even after breaking them into particular clusters.

Androphiliaflag

There were 12 female-female sexual interactions for which we gathered data. The four acts involving anal contact or manipulation were markedly less reportedly exciting than any of the other eight acts. For those other 8, the Heterosexual group always rated these female-female acts as much less exciting than did any of the other three groups (as expected), and average responses of the Bisexual-lesbian group did not differ from those of the Lesbian group. The Bisexual-heterosexual group was intermediate between those more and less lesbian than themselves, or were equally excited by female-female acts as the more lesbian groups were.

Results of the factor analyses are presented in Tables 4 through 7. In each of these tables, female respondents’ data are presented first. Commonalities are listed in the first data column; in almost all cases they exceed 0.5, thus indicating appropriateness for factor analysis. The other columns of data list the factor loadings for each variable (as calculated by the statistics program), with the strongest factor loading highlighted in each row—as well as the names assigned by the authors after examining these strongest loadings and discerning/assigning a meaning for the factor.

Questionnaire Item Score Means and Standard Errors by Sexual Orientation Clusters (Female Participants, Acts With Women)

Examination of this figure shows that for each of the 10 parts of the body, there is never any significant difference between the Bisexual-lesbian group and the Lesbian group. In every case (and not surprisingly), the Heterosexual group always averages significantly lower ratings of female body parts than the other groups. The Bisexual-heterosexual group is sometimes intermediate between the Heterosexual and the more lesbian groups (Lesbians and Bisexual-lesbians), but sometimes does not differ significantly from those more lesbian groups. The interpretation of this pattern (as well as those of the others below) will be left for the Discussion.

Homosexual men are not intrinsically attracted to anal sex. There is a tendency in the popular imagination to equate male homosexuality with an interest in anal sex. In this view, gay men perform anal sex not just because their male partners lack a vagina, but also because they have a specific taste for the practice. This popular opinion is often confusing, as it is even in legal language when a “sodomite” (a male homosexual) may or may not have committed “sodomy” (anal—or in some states, oral—sex). Our data clearly identify this as a misconception. Homosexual men understandably rate anal sex with women lower than the other four groups do, but do not favor anal sex with men significantly more than Bi-homosexual or even Bi-heterosexual men do. As explained under point (6), if there is a group that has an elevated opinion of anal sex per se, it is the Bi-heterosexual group (but modestly so).

Figures 2 through 9 present the means and standard errors for each of the questionnaire items as a function of cluster membership.

The first participants were recruited at a meeting of a social discussion group aimed at bisexuals in a large city in southern California. A second group was recruited in New York by the first author, who attended a large 1994 political event in which many bisexuals participated. In both cases, respondents completed written questionnaires. The rest of the participants were recruited through electronic sources over the Internet: via commercial on-line services’ special interest groups for sexual topics, Usenet newsgroups (such as soc.singles, soc.couples, soc.bi, and alt.homosexuality).

Democratic Republic Congo Flag Images ... Satisfy your creative craving with Adobe Stock. ... Photo democratic republic of the congo flag is depicted on a sports ...

Gynephilia

Bi-heterosexual individuals seem to be somewhat more sexually adventurous than might be expected from their position in the progression from pure heterosexual to pure homosexual. This appears to be true for both men and women, and is clearest in the factors pertaining to anal acts. Often Bi-heterosexual groups rate anal acts more positively than any other group does (they are occasionally joined by the Bi-lesbian women). Very often (albeit not always), the ratings by Bi-heterosexual groups of same-sex stimuli equal those of homosexual group members, and are of course significantly higher than ratings by heterosexual group members. It is very important to note that our original cluster analysis identified cluster membership solely on the basis of the participants’ Klein Grid scores (see Figure 1), a process that did not make any reference whatsoever to anal sex (nor, for that matter, to any particular sex act or part of the body). This is, accordingly, an empirical finding, not a tautological one.

The samples (male and female) were drawn from two sources (see Methods): bisexual meetings and support groups, and through electronic interest groups and newsgroups. These participants certainly do not constitute a random sample of any population. We chose this method of recruitment because we wanted male and female samples spanning the sexual orientation spectrum that would be roughly uniformly distributed across that spectrum.

Note that a corresponding phenomenon did not emerge for the attractions to female body parts. There might have been a contrast factor for “Breasts: small” versus “Breasts: large”, or for “Buttocks: large” versus “Buttocks: small”—but neither emerged in the analyses.

GynephiliaFlagmeaning

These 30 inch printed diamonds have whimsical graphics and ageless appeal. A traditional favorite for all ages, our 30 inch Diamonds look as great for home decoration as they do in the sky.

The answer: They can be shown to emerge from the data. An item such as “I am a nervous person” correlates better with an item such as “I am easily frightened” than it does with an item such as “I am nervous”. (Note: These items are, obviously, inspired by the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, or STAI; Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, 1983.) A factor analysis of a series of anxiety-related items begins with a table of correlation coefficients among those items, and would result in a list of the items’ loadings on each of two unnamed factors—factors discerned by the statistics program in ignorance of the meanings of the items themselves. Human beings would then look at those factor loadings and note that all of the items on Factor 1 (for example) seemed to pertain to a person’s current feelings (“I am nervous”), whereas the others pertained to lasting tendencies (i.e., personality: “I am a nervous person”). [As an aside, if you happen to know the distinction in Spanish between ser (to be, as a trait) and estar (to be, as a condition of the current moment), that’s the state/trait distinction.]

Gynephilia meaning

We believe that this is the first empirical study to report what it is about women and men that forms the basis for attractions to them, and the first to identify significant subgroups among men who are attracted to men.

In a previous paper, we used cluster analysis to empirically assign individual participants to discrete sexual orientation categories in a sample of bisexual, heterosexual, and homosexual men and women (Weinrich & Klein, 1997, the “Main Sample”; also described in Weinrich et al., 2014). The present paper uses that clustering solution to describe various aspects of personality and erotosexual parameters in this sample—and, by extension, perhaps in the world at large. Here we analyze our participants’ erotic preferences for sexual acts and parts of the body.

Concerning male bodies, once again there are almost no differences; only the male genitals elicit significantly different ratings by different sexual orientation groups, and even here the differences are small. This runs counter to the stereotype that women pay more attention to emotional stimuli than to physical ones in their erotic relationships.

The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (Hong Kong SAR) is an inalienable part of the People's Republic of China. The national flag and national emblem of ...

Demographic tabulations for the two samples are presented in Table 3. The sample was a bit under 2/3 male, young middle-aged, and very highly educated. About 1/7 of the participants were currently in a homosexual relationship, about 1/7 were divorced, and about half were single/never married—leaving just over 1/3 as married. About 1/3 were recruited through the bisexual group sampling, 2/3 through the Internet. The women were on average about 4 years younger than the men. Further demographic information can be found in the previous publication (Weinrich & Klein, 1997).

Jul 15, 2024 — SPARTANBURG COUNTY, S.C. - An Atlanta man allegedly made a nearly three-hour-long trek to South Carolina to lower the Confederate flag that ...

The factor structures of men’s and women’s attractions to men (especially men’s bodies) are remarkably different. Affectionate acts with men are the least salient factor differentiating women, and the most salient factor differentiating men (by a wide margin). Moreover, there is remarkably little variation from group to group for women’s ratings of affectionate acts with men—and similarly little variation in their ratings of three of the four categories of parts of men’s bodies! On the other hand, there are always clear and significant differences by sexual orientation group when the men’s ratings of masculine stimuli are considered. This striking difference is yet more evidence that (to overgeneralize a bit) women are more likely to be bisexual than men.

Data were entered into computers, scored, and analyzed using JMP version 3.0.1 from the SAS Institute. As explained in our original paper (Weinrich & Klein, 1997), we performed two cluster analyses (one each by sex) of the 21 KSOG items, using hierarchical agglomerative clustering by participant, and chose a 5-cluster division for the men (into clusters we named “Homosexual,” “Bisexual-homosexual,” “Bisexual-bisexual,” “Bisexual-heterosexual,” and “Heterosexual”) and a 4-cluster division for the women (named “Lesbian,” “Bisexual-lesbian,” “Bisexual-heterosexual,” and “Heterosexual”). For convenience, we will abbreviate these designations from time to time. (In some other presentations, we may have referred to the “Bisexual-homosexual” group as the “Bi-Gay” group, and so on.)

This is a remarkable finding—one that tends to undercut the notion that men attach little significance to affection and love in their relationships. It also runs counter to the stereotype that men pay more attention to physical stimuli than to emotional ones in their erotic relationships. Neither conclusion denies the fact that in the Exhaustive Analyses both erotic and non-erotic variables sharply distinguish the 5 male sexual orientation clusters.

Accordingly, a conservative interpretation of finding (8) is warranted. What should be deemed remarkable is not that the less specifically erotic variables loaded onto the highest-eigenvalue factor, but that in both the data reduced and the exhaustive analyses they were about as important, or perhaps more important, than the explicitly erotic variables were in distinguishing the sexual orientation groups from each other.

Finally, we need to resolve the apparent conflict pertaining to generalization (8). Recall that the data reduced analyses suggested that affectionate acts and nonerotic body parts were more strongly indicative of one’s sexual orientation cluster membership (among men), but in the exhaustive analyses the reverse seemed true. Understanding how factor analysis works helps resolve this contradiction. A factor analysis groups variables into factors (like sorting playing cards into separate piles) based upon which variables have the strongest co-variation (across participants). If two variables are sorted into the same factor, then knowing a participant’s score on one of the variables gives you a good guess as to her or his score on the other variable—but tells you little or nothing about his or her score on a variable not loading primarily on that factor. Once the strongest factor is identified, variance associated with that factor is removed from the dataset and the next-best factor is calculated.

Bisexuals are neither consistently intermediate between homosexuals and heterosexuals nor consistently similar to homosexuals and heterosexuals. For example, consider women’s ratings of women’s body parts (first two charts in Figure 10). In one chart, ratings by members of the bisexuals groups appear to be intermediate between those of the heterosexual and homosexual groups, thus suggesting that bisexual groups are “in between” the two endpoint groups. In the other chart, ratings by both bisexual groups are very similar to those of lesbian endpoint, not intermediate between the two endpoints. After careful consideration and searching, we have not been able to come up with any generalization that would accurately describe bisexuals as a whole, or particular bisexual subgroups, as either a simple intermediate between homosexual and heterosexual endpoints or as a simple combination of the two endpoints.

The factor structures of men’s and women’s attractions to women are remarkably similar. For both male and female respondents, anal sex acts loaded onto a different factor than other sex acts—and that was all. No finer distinctions emerged.

With regard to feminine stimuli (women’s bodies and acts with women—top half of Figure 10), mean cluster scores of female respondents revealed interesting patterns. The sex acts with women were rated as highly exciting for the Lesbian and both Bisexual clusters, and were scarcely at all exciting to the Heterosexual cluster. Acts involving anal contact were far less exciting. There was, however, a small but statistically significant tendency for the two bisexual groups to report slightly higher levels of excitement pertaining to the acts that constituted the anal sex factor. With regard to the female body itself as an erotic object, the three non-heterosexual groups were equally excited by the erotic parts of a woman’s body, with the Heterosexual cluster of course lagging behind. When it came to the not-so-erotic parts of a woman’s body, there was a straight-line relationship (nearly linear) of reported excitement to sexual orientation cluster membership.

When this paper was being prepared, the principal support for Dr. Weinrich came from the Universitywide AIDS Research Program of the University of California (grants R93-SD-062 and R95-SD-123). He worked at the HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center (HNRC), which was supported by NIMH Center grant 5 P50 MH45294.

Size (W X L): 32 x 30 in. / 81 x 76 cm. Wind Range: 5 ~ 15 mph Fabric: Nylon Frame: Fiberglass and Hardwood Dowels Line: Includes 300 ft. of 20 lb. Test Line and Winder All 30 inch Diamonds include tails.

For the exhaustive set of analyses, we calculated means and standard errors for each of the 9 groups of participants on the 50 dependent variables from the questionnaires. These pertained to preferred sexual acts and sexually arousing body parts.

These 30 inch printed diamonds have whimsical graphics and ageless appeal. A traditional favorite for all ages, our 30 inch Diamonds look as great for home decoration as they do in the sky.

For the sex acts with men (Table 7), 3 factors emerged (essentially identical in male and female subsamples, albeit in different order)—which we termed Sexual acts (oral sex, breast/chest stimulation, vaginal intercourse, etc.), Affectionate acts (kissing, cuddling), and Anal acts (digital-anal contact, oral-anal activity, and anal intercourse).

This paper is one in a series of papers conceived by the authors back in the 1990s. It is presented here not as a definitive, up-to-date review of the literature, but as a quasi-historical document that captures a new way of conceptualizing and measuring sexual attractions. What follows is, for the most part, the original manuscript as it was drafted by the two authors back in the 1990s. We conceived and carried out data collection, and began data analysis, on one of the first samples of people from across the sexual orientation spectrum recruited (in part) from the Internet. As a result of a series of life events (including the death of coauthor Fritz Klein in 2006), few of these papers have been actually written, and the book never passed out of the planning phase. However, four papers were actually written using this data set, two of which have been published previously (Weinrich, Snyder, Pillard, Grant, Jacobson, Robinson, & McCutchan, 1993; Weinrich & Klein, 2002), and the third is published elsewhere in this issue (Klein & Weinrich, 2014). The present paper, then, is the fourth and last of the papers actually prepared while Dr. Klein was alive, and has been only modestly revised by myself after his death. Papers in this series should be regarded as resulting equally from the intellectual contributions of the two authors, who agreed to exchange first and second authorship with each successive publication.

This distinction may be an important one in the male gay/bisexual community. For example, all four of the groups of male participants who are not completely heterosexual reported significantly more excitement by the Genital/Ephebephilic factor than the Heterosexual group did. But only the two groups at the homosexual end of the spectrum reported significantly higher excitement due to the Androphilic factor. As we mentioned in passing in the Results section, we speculate that many of the men in the bisexual clusters may have been aroused by the ephebephilic body type because it is not too different from the feminine body type.

(10) Although all groups of women generally give low ratings to oral-anal contacts, ratings of oral-anal contacts are particularly low among lesbians—including oral-anal contact with women. This is in contrast with the patterns for anal fingering which, while likewise of low general popularity, lesbian women favor to about the same extent as Bi-lesbian and Bi-heterosexual women do.

(6) Bi-heterosexually-oriented individuals of both sexes often seem more sexually adventurous than might be expected from their position in the progression from Heterosexual to Homosexual or Lesbian.

Sexual orientation is one of sexology’s thorniest concepts (Weinrich, 1987/2013). Seemingly simple—is someone sexually attracted to or aroused by members of her or his own sex, or by the other sex?—it is philosophically extremely complex (Klein, 1993; Shively & De Cecco, 1977). How are homosexuality, heterosexuality, and bisexuality properly defined? Once defined, how are they characterized? Are bisexuals intermediate between homosexual and heterosexual endpoints? Or is bisexuality in some sense a combination of homosexuality and heterosexuality, with bisexuals enjoying the best of both worlds—perhaps (as Woody Allen suggested) with twice the likelihood of getting a date on Saturday night?

For both genders, the specifically affectionate and sexual acts were more salient than the anal acts, as evidenced by the far higher eigenvalues associated with the Sexual/Affectionate factors than the Anal sex factors.

(7) Homosexual men are not uniquely or intrinsically attracted to anal sex. Anal interactions of every type with women received very low ratings, and anal contact with men was rated no more exciting than it was by the various bisexual male participants.

Understanding bisexuality is the key to understanding sexual orientation. On many sexual orientation measures, bisexuality is intermediate between homosexuality and heterosexuality, as it is in the widely-used “Kinsey scale” (a bipolar scale ranging from 0 to 6; see Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948; McWhirter, Reinisch, & Sanders, 1990). In a bipolar measure the two poles can only be averaged, not combined (e.g., no one can be both tall and short with respect to the same measure at the same time). With other definitions, bisexuality is a category applied to individuals who have high levels of sexual interest in both men and women. (This is analogous to the “androgynous” category of Bem’s masculinity and femininity scales: Bem, 1981.) In this latter view, bisexuality is the combination of homosexuality and heterosexuality, not a compromise between the two. Even more intriguing is the possibility that bisexuality is not properly defined merely with reference to homosexuality and heterosexuality—if, for example, the personal freedom to be attracted to either sex were associated with a taste for more (or less) exotic sexual preferences and practices as well.

Internet volunteers received the questionnaire via e-mail, completed it, and returned it (typically, also by e-mail). More anonymous methods involving faxes and ordinary mail were also used.

Questionnaire Item Score Means and Standard Errors by Sexual Orientation Clusters (Female Participants, Bodies of Women)

As above, acts involving the anus were least popular across all groups, although the Bisexual-heterosexual cluster (arguably) seemed to prefer them a bit more, on average, than the other three clusters. Members of the Lesbian group of course rated the remaining male-female acts significantly less exciting in each case than did their more bisexual or heterosexual cohorts. Note, however, that the Lesbian group also had by far the largest standard errors for each of the 9 non-anal acts, suggesting that a subgroup of that cluster is aware of substantial heterosexual responsivity. Remarkably, for cuddling/holding there were no significant differences among the four clusters, and barely any differences for kissing. (As shown below, this pattern is most emphatically not mirrored in the corresponding male data—male participants, acts with men—in Figure 9.)

As a technical aside, note that factor analyses do not produce significance estimates (p-values). Consider a hypothetical sample, imagined to be insignificantly different from ours, which is slightly more biased toward correlations among specifically erotic and genital measures. In such a sample, the erotic/genital items might have turned out to load on the factor with the highest eigenvalue. That said, it is important to note that the affectionate/nonerotic factor was much stronger than many people might have expected it to be.